Two Species, One Mother

The world of insects is a bizarre place where it seems every rule has an exception. You've got frog-eating beetles, vampire moths, city-building cockroaches and the unholy spawn of a wasp and a praying mantis whose children exclusively eat the eggs of spiders, and that's just the tip of the iceberg. But a new paper reveals something truly bizarre about a seemingly humble, ordinary insect: the Iberian harvester ant, Messor ibericus.

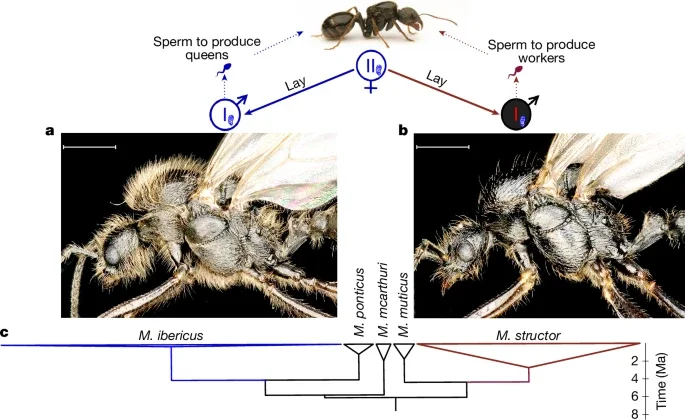

Hairy M. ibericus male ant vs. hairless M. structor male ant. Though they look similar to our eyes, they are separated by more than 5 million years of evolution.

Juvé, Y., Lutrat, C., Ha, A. et al. (2025)

M. ibericus is an unremarkable species of ant which excavates great nests in pastures and forests across much of Europe. They don't look all that different from your usual playground ants and live much the same way, collecting seeds, nectar and insects to feed their colonies. But scientists recently discovered that Sicilian M. ibericus are more than meets the eye, having developed a truly bizarre relationship with another Messor species: the common European harvester ant M. structor.

In many parts of Europe, M. ibericus and M. structor coexist and occasionally interbreed. But scientists studying the these interbreeding patterns noticed something strange: on the island of Sicily, they found flying male ants of both species. But no matter how hard they looked, they weren't ever able to find a colony of the M. structor. And when they decided to dig up a couple M. ibericus colonies, they found something shocking. Among the M. ibericus workers, queens and males were male M. structor! This is extremely unusual, as ants are usually violently intolerant of ants from other colonies of their own species, let alone those of another species entirely. Yet the M. ibericus workers displayed no aggression towards the M. structor males, cleaning and feeding them just as they did for their own nestmates.

The puzzled researchers decided to do some gene sequencing to find out what was going on. Perhaps these strange male ants were simply an unusual morph of M. ibericus, not M. structor? But the results of the sequencing only deepened the mystery. It turned out that the workers in the Sicilian M. ibericus colonies was not actually M. ibericus, but rather M. ibericus/M. structor hybrids! The queens and ordinary males were purely M. ibericus, while the strange males were pure M. structor. But, most shockingly, a single queen was able to lay eggs of both M. ibericus and M. structor males!

Another species which must steal the genes of others: Edible frog Pelophylax kl. esculentus, which mates with pool frogs P. lessonae to reproduce.

Helge Busch-Paulick (CC BY 3.0)

With further testing, the bizarre life cycle of M. ibericus was fully elucidated. It turns out that M. ibericus queens can only produce hybrid workers using the sperm of M. structor—pure M. ibericus females only grew into queens. M. ibericus queens in areas where M. structor also lives will mate with both male M. ibericus and male M. structor, ensuring that they can make both a workforce and their royal successors. But whern M. ibericus moved into areas where M. structor did not live, they have a clever solution: some of the hybrid eggs fertilised with M. structor sperm would jettison the M. ibericus genome, resulting in M. structor males genetically identical to their own fathers. And indeed, these cloned male M. structor are found throughout southern Europe, everywhere where M. ibericus lives but M. structor does not.

This kind of system, where one species must mate with another to complete its life cycle, certainly seems bizarre. But the researchers who discovered it have an idea of how it might have evolved. The loss of the ability to make workers with M. ibericus sperm may have originally been a rare, defective mutation, but M. ibericus queens with the mutation who mated with M. structor were able to rescue themselves by making workers with the fully functional M. structor genome. The mutation spread, either by chance or because it conferred some other advantages, and eventually all M. ibericus had to mate with M. structor to make workers. Another mutation eventually allowed some M. ibericus queens to clone M. structor males, freeing them from their species's dependence on M. structor and allowing them to colonise habitats where M. structor did not live. While it may have made more sense for M. ibericus to have kept its ability to make workers, the M. structor male-cloning system worked well enough to persist. M. ibericus is thus an excellent example of constructive neutral evolution: 'survival of the good enough', where a complex life cycle evolved not because it was better than the alternative, but because it was simply not worse.