Our Spineless Cousins

A small colony of bluebell tunicates (Clavelina puertosecensis).

Pauline Walsh Jacobson (CC BY 4.0)

We vertebrates can be really self-centred sometimes. We call ourselves 'higher animals' and draw little cartoons of worms turning into fish turning into men on an endless march of evolutionary 'progress'. We boast of our big brains and our dextrous hands as if they were divine gifts and not just another quirk among the vagaries of evolution.

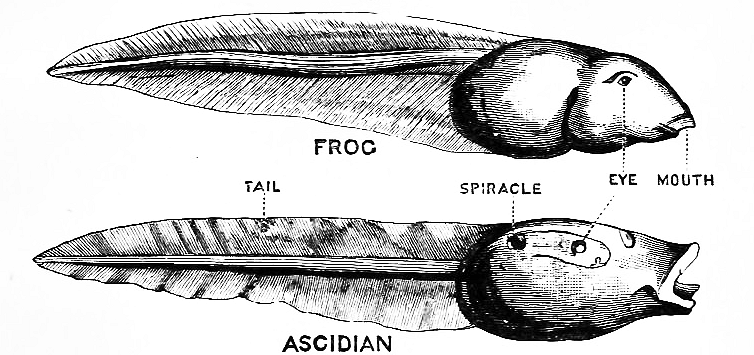

Tunicate larva versus frog tadpole. The resemblance is uncanny.

British Museum (Public Domain)

Given that overinflated confidence, it might be a little embarassing to learn that our closest invertebrate relative is not something like a smart octopus or a powerful crab but rather an animal which took its life advice from the humble sponge and permanently stuck its head to a rock.

So, tunicates! Also known as sea squirts, sea pork, sea tulips and a variety of other names based on the appearance of particular species, these are exclusively marine invertebrates native to oceans across the world, from tropical reefs to the deepest abyss. The vast majority of them are filter-feeders, breathing in water using one of their two , straining out edible plankton with internal filter baskets, then sending the water out of the other siphon. They cloak themselves in an exoskeleton ('tunic') made of cellulose, the chemical that plants use to make wood, having stolen the genes to make it from bacteria1. Most live attached to rocks, seaweeds, boats, corals or other surfaces, but some have learned to swim and live out in the open ocean. They can be solitary, living alone as individuals, or colonial, aggregating into hundreds or thousands-strong groups united by a shared tunic.

Doliolid colony. The big, barrel-shaped zooid is for moving, while the little green ones are for eating.

Pierre Corbrion (CC0)

It would be fair to say that they look nothing like us. And yet, genetic studies confidently identify them as the closest cousins of vertebrates, united as a group called the Olfactores2. But how is this posssible?

While most adult tunicates show little trace of their ancestry, it becomes painfully obvious if you look at their whole life cycle. For when tunicates emerge from their eggs, they are little swimming critters that look almost exactly like the tadpoles of frogs, complete with eyes, fins, gills and even a notochord3, a cartilaginous rod which in most vertebrates becomes the spinal column. But the tunicate larva is on a race against time, as it has no functional gut and lives off of the meagre helping of egg yolk afforded to it by its mother. In the time before it starves, it must find a suitable surface to call home. Once a substrate is found, the tunicate larva affixes itself with a glue secreted from its lips and gets to work reshaping itself. The eyes, fins and notochord are digested, for it will never swim again, while the gills grow and expand into the filter basket it will use to catch food for the rest of its life3. Except for the iconic deep-sea predatory tunicate Megalodicopia hians, who ditches the filters and grows a giant fleshy maw that engulfs small shrimp and fish like a nightmarish cross between sock-puppet and Venus flytrap.

Bathochordaeus larvaceans in their houses.

Sherlock, R.E., Walz, K.R. and Robison, B.H. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Now there are some tunicates who do not care for all this fishy business. The Thaliacea, commonly known as salps, pyrosomes and doliolids, are one of two types of tunicate. Most lack a larval stage entirely, hatching out of their eggs already in their lumpy, pickle-shaped adult forms3. But they are no slouches when it comes to strangeness. Pyrosomes are almost microscopic but form colonies millions strong that undulate through the water like eerie sea serpents, flashing with brilliant that can set the seas 3. Salps are much larger and engage in a bizarre , with solitary, fish-shaped oozoids that give live, virgin birth to chains and rings of colonial blastozooids, who start life as egg-laying females then transition into males before inevitably dying when their filters get clogged3. And weirdest of all are the doliolids, who decided to copy the homework of the Portuguese man' o war and developed colonies with all kinds of which each specialise for a task like swimming, eating or reproducing3.

But the other kind of pelagic tunicate is arguably even weirder. The Appendicularia, or larvaceans, are exactly what it says on the tin—they never grow up like Peter Pan, keeping their fins and notochords as they swim the open seas3. Without powerful siphons and filter baskets they construct intricate mucus 'houses' to do the hard work of filter-feeding, complete with sieves to keep out inedibles and escape hatches to dodge predators4. They're so good at filtering that they have to discard their houses every few hours simply because they clog up with too much food, which they leave to scavengers waiting on the ocean floor below4. They can even remove microplastics from the water5 (thanks, larvaceans!). But in spite of all their success, never growing up does pose one terminal issue: they never develop a reproductive tract and have no way of laying their eggs. To reproduce, they must rip open their own skin and toss their ovaries out into the ocean, which invariably kills them3. Accordingly, larvaceans are here for a good time, not a long time, going from egg to adult and reaching their grisly self-inflicted ends in just a week or less3.

Megasiphon thylakos.

Karma Nanglu, Rudy Lerosey-Aubril, James C. Weaver, Javier Ortega-Hernández (CC BY 4.0)

Now, it's been traditionally thought that the earliest tunicates lived much like the larvaceans do today, floating in the open sea and filtering plankton for food. If this is true, then larvaceans aren't really larvae that don't grow up—they'd just be primitive-looking adults6. But a pair of curious fossils might indicate otherwise. The ordinary-looking tunicate Megasiphon thylakos was found in rocks 500 million years old, well before larvaceans show up in the fossil record6. If it is indeed more primitive than them, then that would mean that the earliest tunicates looked more like Megasiphon6, and larvaceans really are larvae that don't grow up, having lost their adult stage over the course of evolution.

But there is one more fossil that may indicate that larvaceans weren't the only ones who ran away to Neverland. Shankouclava anningense is a tunicate-like animal from about 518 million years ago, a little older than Megasiphon7. But unlike Megasiphon, Shankouclava doesn't look all that like modern tunicates: it's got the siphons and the filter basket down, but it's also got a long, fleshy stalk that anchors to the seabed7. And while we're not exactly sure where exactly Shankouclava lies on the tree of life8, some scientists have proposed that it's a primitive member of Olfactores6—an ancestral stock from which both tunicates and vertebrates evolved. If this is true, then that means that we ourselves are also larvae that never grew up6, our fishy ancestors turning their stalks into swimming tails and gallivanting around the open seas instead of settling down on a rock and starting a family like any respectable olfactorean ought to.

Of course, this is still just a hypothesis—lancelets, vertebrates' next-closest relatives after tunicates, don't bother with metamorphosis at all, so it's still unclear what exactly the earliest members of our lineage were doing. But I think it'd be pretty funny if the supposed 'pinnacles of evolution' were just dumb kids who never grew wise to the ways of the world.

References

1 🔒Sasakura, Y., Ogura, Y., Treen, N., Yokomori, R., Park, S.-J., Nakai, K., Saiga, H., Tetsushi, S., Yamamoto, T., Fujiwara, S., & Yoshida, K. (2016). Transcriptional regulation of a horizontally transferred gene from bacterium to chordate. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 283, 20161712. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.1712

2 🔒Delsuc, F., Brinkmann, H., Chourrout, D., & Philippe, H. (2006). Tunicates and not cephalochordates are the closest living relatives of vertebrates. Nature, 439, 965–968. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04336

3 📖Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S. & Barnes, R.D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology. (7th ed.). Cengage Learning.

4 Katija, K., Sherlock, R. E., Sherman, A. D., & Robison, B. H. (2017). New technology reveals the role of giant larvaceans in oceanic carbon cycling. Science Advances, 3(5), e1602374. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1602374

5 Katija, K., Choy, C. A., Sherlock, R. E., Sherman, A. D., & Robison, B. H. (2017). From the surface to the seafloor: How giant larvaceans transport microplastics into the deep sea. Science Advances, 3(8), e1700715. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700715

6 Nanglu, K., Lerosey-Aubril, R., Weaver, J. C., & Ortega-Hernández, J. (2023). A mid-Cambrian tunicate and the deep origin of the ascidiacean body plan. Nature Communications, 14, 3832. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39012-4

7 Chen, J.-Y., Huang, D.-Y., Peng, Q.-Q., Chi, H.-M., Wang, X.-Q., & Feng, M. (2003). The first tunicate from the Early Cambrian of South China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100(14), 8314-8318. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1431177100

8 🔒Morris, S. C. (2006). Darwin's dilemma: the realities of the Cambrian ‘explosion’. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 361, 1069–1083. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2006.1846

----------

🔒Closed-access article

📖Book